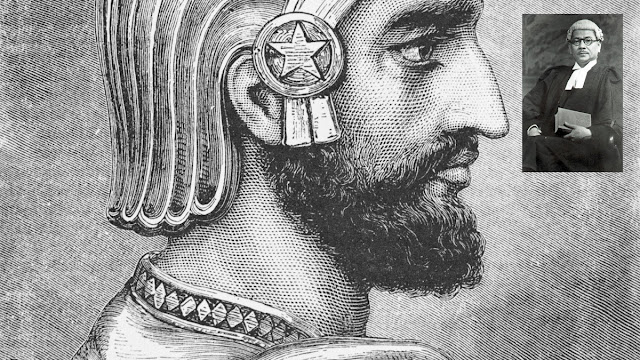

Cyrus & Tunku

Cyrus & Tunku was published by Tommy Peters Bicycles on January 24, 2016

“A good design is obvious. A great design is transparent.”

The maxim holds for King Cyrus of Persia and Tunku Abdul Rahman of Malaysia, who promoted a great design in a multicultural fabric working ‘transparently’ in the background.

In 500 B.C. King Cyrus, who wrote the first human rights charter, kept religions private and ethnicities distinct, enabling the ‘racehorse’ and ‘plough-horse’ to co-exist seamlessly. Generally, the Persians represented racehorses and Arabs, the plough-horses working in tandem to better the empire and down the pike; in modern times, they perform similar roles where the former is as an ‘entrepreneur’ and the latter a ‘consumer.’

Cyrus recognised that the pursuit of ethnic integration is the destruction of excellence, in that “for a plough-horse to keep up with a racehorse he would have to cripple the racehorse and conversely, for a racehorse to pull as much as a plough-horse, he would have to cripple the plough-horse.”

Result: Ask an Egyptian, Syrian, Jordanian, Iraqi, Libyan, or even a Saudi, and they would ponder surprisingly that Persians once ruled over them. Cyrus’s ethnic unity over ethnic integration principle enabled ethnicities in his domain to remain recognisably distinct and nationalistic. Twenty-eight countries he commanded were oblivious of their previous Persian masters because the King ensured by decree that individual religions and cultures thrived autonomously under his reign. There is no record of him appropriating a single place of worship of another religion for conversion to Zoroastrianism, the de facto Persian dogma. However, there were many opportunities for him to do so. He not only recognised the value and effect of religions and ethnicity, but he also promoted them.

Wittingly or otherwise, Tunku promoted the same principles. He kept religion out of the public domain and encouraged ethnic education, festivals, and politics under Malaysia’s secularist umbrella. As Cyrus did, he pushed for ethnic unity over ethnic integration.

Result: Races in Malaysia reside side-by-side in a glorious fabric, recognisably distinct in features, mannerisms, food consumption, accents, and even cuss words.

Ethnic integration is a good design, but it summons the lowest common denominator that cripples the racehorse in favour of the plough horse. In contrast, ethnic unity is a great design that creates a stable of racehorses working seamlessly with the plough horses in tandem.

“A good design is obvious. A great design is transparent.”

Peace!

Tommy Peters

Comments

Post a Comment